The above picture came from The Children of the Manhattan Project website

Articles above and below scanned by Burt Pierard ('59)

The following was offered by Beth Young Gibson ('81)

The East Benton County Museum published them in their quarterly newsletter.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Columbia Camp, Prison Camp in our Midst, 1944-1947, Jean Carol Davis, The Courier, East Benton County Historical Society, Volume 15, Number 1, February 1993.

Columbia Camp, at the horn of the Yakima River, opened February 1, 1944, by Federal Prison Industries for "minimum-custody-type improvable male offenders," who had no more than one year to serve. They were violators of national defense, wartime and military laws. Included were conscientious objectors, violators of rationing and price support laws, those convicted of espionage, sabotage and sedition and by military courts martial. Aliens who failed to register were in this category but none of them were sent to Columbia Camp because of the Hanford project.

The 25-acre camp was located between Horn Road and the Yakima River. (The row of trees which can be seen today was on the westerly boundary.) The camp was built by the Manhattan District, Corps of Engineers, or under contract to them, using former Civilian Conservation Corps buildings moved from Winifred, Montana. These included five barracks, office building, hospital, mess hall, storage and utility buildings and a recreation hall. Three buildings of the same type were moved from White Bluffs where they had been erected for use in the Hanford construction staging area along the Milwaukee Railroad. In addition, the camp had five double hutment type barracks, 10 prefab houses and 12 single hutments used for housing of prison executives, guards and their families. "Hutments" was the term for the fabricated temporary buildings which later were referred to as Quonset huts because the first of that type in this country had been built at Quonset, Rhode Island.

Under a wartime contract with Hanford, Federal Prison Industries operated workable orchards and vineyards. Fruit was shipped to the McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary near Tacoma, where it was processed (most of it canned) for sale to military services and other government agencies. When the contract ended November 1, 1947, 5,669 tons of fruit had been processed which sold for more than $500,000.

Statistics from the Federal Bureau of Prisons show that a total of 1,300 prisoners served at Columbia Camp with 290 being the maximum at any one time. A memorandum from the Bureau of Prisons archives dated March 8, 1944, noted: "Selection of inmates for Columbia Camp is of great importance because the Army Engineers have there a secret military project which they are trying to guard very zealously. We agreed with them to select inmates carefully and give them criminal data on every inmate selected." A further suggestion in the memo was that criteria be set up for selection of inmates for this camp and that there be a careful review of the inmate's entire record including interview, medical, and work records.

It was commonly believed that most of the inmates were conscientious objectors but Bureau of Prisons statistics show that they made up less than 30 percent of the total who were there. Several comments suggest that the conscientious objectors were discriminated against to some degree. The depth of patriotism those years lends credence to the likelihood that this was true. Kay Weir Fishback remembers that her parents, permitted to lease back their home in Richland, recalled that when two men came to check the irrigation, one of them stressed that he was not a conscientious objector and that his son was serving in the army.

About forty guards and other staff lived at the camp, some with their families. Many had been transferred from within the federal prison system. Some local people were employed as support personnel. No one has been located who actually lived or worked there when Columbia Camp was operated as a prison.

Siblings Elvera Stephens, Doris Barott, and John Hackney lived in the only house within some distance of Columbia Camp. Their father worked for the irrigation company. Their home was across the river and downstream about one-half mile from the camp near Horn Rapids dam. Doris commented that it had been so quiet in the country that they were conscious of sounds coming down the river, such as a dog bark, voices, vehicles and the like. Their only contact with Columbia Camp was with school friends whose parents lived in the staff housing. Occasionally friends would come by boat to visit. Elvera told of the time some of them came to raid the Hackney melon patch. Mr Hackney fired a gun into the air. In their haste to get away, the leaky boat capsized and the boys had to swim. John recalls that one winter the river was frozen over and he walked across the ice to visit. They would sometimes see inmates walking around the camp or fishing in the river.

Prisoners were transported to the orchards to prune, spray, cultivate, and irrigate and then to harvest the fruit. Army vehicles carrying 25 to 30 passengers were used. Others were borrowed from the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) motor pool because that agency had the highest priority to obtain available vehicles. F I McHale, then Director of Security for the Manhattan District, Corps of Engineers, and later for the ARC, told of Chevrolet cars being cut in two and extended to become "stretch limousines" for transport. One guard accompanied five to ten inmates.

Monsignor William J Sweeney recalled that he went to Columbia Camp to say Mass each Monday morning, setting up an altar on a table in a commons room. About ten men attended Mass. Father Sweeney stayed for breakfast after the service. He remembered that the food was very good and that everyone was especially kind to him.

Only twelve inmates escaped from the facility in the nearly four years it was in operation. That there were not more is surprising because there was no fence along the Yakima River and the inmates' work in the orchards was difficult to supervise.

Guard Joe Rice and his wife lived next door to Homer Moulthrop in the old Amanda Breithaupt house on the corner of George Washington Way and Falley Street, which still stands. Homer said that they visited and played chess together but did not ever discuss their jobs. One night loud knocking on the Rice s door roused Homer. He later learned that prisoners had escaped and off-duty personnel were being called to help with the search.

Harley and Joyce Sweany of Benton City discovered footprints on their land along the river at Kiona after learning that some prisoners had escaped. They were caught before reaching Prosser. These may or may not have been the same incident.

John Hackney remembers that one fall enroute to school on the bus that the students saw some inmates that had climbed high into the fruit trees and were temporarily missed by their guard.

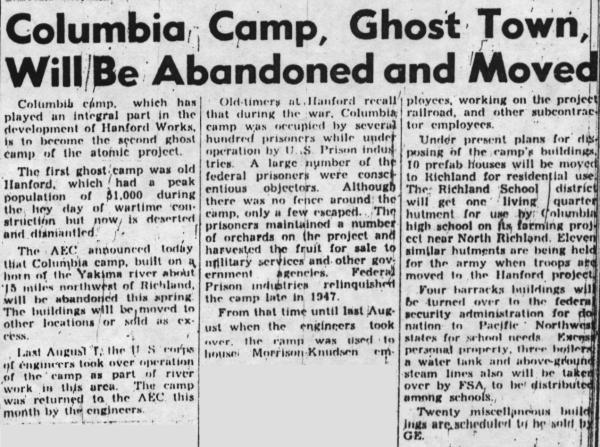

Columbia Camp closed October 10, 1947, when no longer needed. Continued construction on the Hanford project and in Richland had reduced the orchard lands as well as the irrigation canals serving the district. Remaining orchards were contracted to two private concerns to continue work for a percentage of the gross in return for the fruit.

The camp facilities were next used by Atkinson-Jones to house workers while North Richland was constructed. From early 1948 through July 1949 Morrison-Knudsen occupied the camp while constructing and maintaining the Hanford project railroad. Several former Morrison-Knudsen employees live in the area and recall the comfortable, self-contained facility.

Columbia Camp was taken over by the US Corps of Engineers under agreement with the Atomic Energy Commission on August 1,1949, to house personnel working on levees along the Columbia River in the Kennewick and Richland area, as part of the McNary Dam project. In February 1950 AEC announced that Columbia Camp would be abandoned that spring.

General Electric was to handle disposition of the facilities. The ten prefab houses would be moved to Richland for residential use. One living quarter hutment (a Quonset three-bedroom home) went to Richland school district for use by Columbia High School on its farming project near North Richland. The eleven similar hutments were to be held for the army when troops were moved to the Hanford project. Four barracks buildings would be donated to Pacific Northwest states for school needs. Excess personal property, three boilers, a water tank and above ground steam lines would also be distributed among schools.

Twenty miscellaneous buildings were to be sold by General Electric. We have learned about two of them. Bob Baron recalls that his family's house moving firm moved some of the buildings. A large building, probably the recreation hall, was taken apart and reassembled in West Richland for the Community Building on Van Giesen Avenue west of the market, now Mel's Thrift. This building was later razed.

The Benton City Methodist Church at 906 9th Street was constructed in part with materials from the large maintenance building located near the road on the north side of Columbia Camp. It appears to have been built on site rather than from prebuilt panels. Church members dismantled the building and moved the material. Church historian Joyce Sweany found that they had obtained 30,000 board feet of lumber but no other details were recorded.

Bill McKenna, now of Benton City, participated in a Boy Scout Camporee at Columbia Camp in 1951. A large pile of debris, left from clearing of the camp after the structures were removed, burst into flame. All Scouts were confined to their tents until those responsible had confessed. Bill said someone must have done so, otherwise they would still be in those tents.

In 1966, the Columbia Camp site, with other land, was transferred to Benton County by the Bureau of Land Management and is now a part of Horn Rapids Park.

References In addition to those cited in the text, two newspaper articles provided the details of source and disposition of buildings and occupancy of the camp. They are:

Tri-Ciyy Herald, August 7, 1949, p 1

Pasco News, February 24, 1950, p 13

Columbia Camp Revisited, Jean Carol Davis, The Courier, East Benton County Historical Society, Volume 15, Number 3, October 1993.

This article updates aprevious article on Columbia Camp (Courier, February 1993), the wartime prison camp along the Yakima River, whose inmates harvested the fruit from the orchards after the government acquired all of the farm land for the Hanford Project. An intrepid staff writer for the Tri-City Herald reprinted an abridged version of that article in the August 22 issue of that newspaper, along with an article about an Italian prisoner of war camp. The Herald article prompted calls to the author from two Tri-Citians who had lived and worked at Columbia Camp.

Judy Hess Richards of Pasco was born there in 1945, the only child born to a family living at Columbia Camp. She connected the author to her mother, Ama G Peck, now of Yachats, Oregon. Gene Polk of Richland was employed at Columbia Camp from 1946 until it closed in October 1947.

Their stories follow. Others with additional information about Columbia Camp are advised to contact the Historical Society or the author at 582-2242.

George E. and Ama 0. Hess, with five-month old daughter Sandy, were among the first five families to move into Quonset hut homes at Columbia Camp in January 1944. They had come from Roseburg, Oregon where George had farmed in partnership with his father and was a partner in a cannery with a friend, Fred Hurd, then of Olympia. In Washington, D.C. on business, Fred learned of Bureau of Prisons plans to manage orchard lands taken over by the Corps of Engineers and called George to tell him about it. Fred Hurd accompanied four officials to the Richland area to select the camp site. He told of seeing rattlesnakes on a ridge and of Indians fishing at Horn Rapids and drying split salmon on racks. The men purchased a salmon from the Indians, the best that they had ever eaten. George sold the cannery in Roseburg and prepared to move to what was to become Columbia Camp.

George was Field Supervisor with responsibility for all aspects of orchard and farm management for the entire time the facility was in operation. Under his supervision were fifteen foremen and nine truck drivers and farm helpers as well as all of the inmates assigned to field operations. There was a smaller staff fewer inmates, mostly trustees, the first season while Columbia Camp was being established.

Ama Peck recalls the sand and dust and rattlesnakes. Security was tight. Any guests, even dinner guests, had to have clearance. George had Q clearance and one day took Ama to the construction area. She observed workers pouring lead and recalled an article about splitting the atom in Popular Mechanics magazine in the 1930s which she had then shared with her scientific minded 7th grade students. When she went to play bridge with other Camp wives, she remarked that she knew what they were doing that they were preparing to split the atom. When she arrived home that afternoon, three FBI agents were waiting for her and questioned her for an hour-and-a-half. She believes that the Lieutenant's wife had called her husband thinking it was funny that Ama would make such a silly suggestion.

One inmate was especially remembered. He was a handyman around the camp, doing repairs, helping with the gardens and the like. Many mornings, baby Sandy would be put in the back yard and he would come to play with her. Ama enjoyed visiting with him. He was there for nearly two years and had no visitors all that time. Ama believes that he was "taking the rap" for someone else who had violated a wartime law. When time came for his discharge, a leather suitcase was delivered with a fine quality tailored suit for him to wear. A limousine picked him up and he was driven to Yakima where a chartered plane was waiting.

Inmates at Columbia Camp were screened and the majority served their time without incident as this was considered a more desirable place than other prisons. Bureau of Prisons statistics show that only twelve men escaped from Columbia Camp. Ama clearly remembers two incidents of prisoners escaping.

Once, an inmate was digging an irrigation line in Richland and stole some women's clothing from a clothesline, took a bus to Yakima and signed on as a cook at a hop yard. A supervisor suspecting that the cook was male informed "her" that "she" would have a new roommate, the supervisor s daughter. This so unnerved the escapee that he promptly gave himself up!

Later, in 1946, the Hess family moved to the house on the old Snively place on Grosscup flats which had been vacant for about two years after being taken over by the government. During one prison break, all employees were put on round-the-clock duty until the escapees were located. With her husband on such duty, guards periodically checked on Ama and the little girls. Ama was instructed to carry her gun at all times and to shoot if she saw an escapee. She had learned to handle a gun as a youth and had, while at Columbia Camp, taken firearms training, which was optional for family members. She hid her gun in a clothes basket which she carried with her constantly for the two or three days until the men were captured. They were found hiding in a harvest machine in a field, discovered by their footprints after they had stolen milk at the riding academy.

When Columbia Camp closed, the Hess family moved to Richland and then to Kennewick in 1948. George died in 1955 and a few years later Ama remarried. Many Kennewick residents may remember Ama G Hess Peck as she taught arts and crafts at Fruitland and Eastgate grade schools and also at the Junior High school, before retiring in 1973.

Gene Polk arrived at Camp Hanford on July 4, 1944, serving there until discharged from the Army at Fort Lewis in 1946. He returned to Richland and applied for work at Columbia Camp. His first job was as one of three drivers hauling fruit to McNeil Island. The semi-trucks were each loaded with 520 boxes of fruit. To keep the fruit as cool as possible, they left at night to drive over Snoqualmie Pass, waited at Steilacoom for the first morning ferry to McNeil Island, where the trucks were backed up to the cannery. While the fruit was being unloaded, the drivers slept.

After the 1946 harvest season, Gene was put in charge of the vehicle maintenance shop and several inmate helpers. He said that they were all good workers and did nothing to cause their being returned to McNeil Island. He was expected to review their files to be sure that there was no discrepancy between their record and their casual conversations at work.

One of the last three employees at Columbia Camp as it was being closed, Gene applied for a job with General Electric, was accepted, and began there following his last day at Columbia Camp, never missing a day of work. He and his wife lived in a B house in Richland as there was no vacant housing at the camp.

Gene Polk still has vivid memories of the Paul Bruggeman ranch at Vernita and will never forget the beautiful rock home and the well maintamed farm. The farm was immediately to the east of the present entry to Vernita Bridge, extending to the river.

"My Job at Columbia Camp" By George E Hess

Taken from a job description written up by the late George E Hess (see preceding article.)

Columbia Camp is a Prison Camp assigned to the task of maintaining the orchards, vineyards and farm land on the Hanford Atomic project for the Army. Also to perfrom other maintenance, repair and minor construction operation for the Army.

Inmates of the camp, under the direction of civilian foremen, are used to perform this work. The use of inmates in the operation is to provide for the vocational training and rehabilitation through actual on the job performance.

As Field Supervisor my duties and responsibilities are:

1. Planning, coordinating and directing farming and other activities in conjunction with the camp Superintendent, the Industrial Business Manager and the Area Agronomist.

This requires knowledge of and actual experience in, all phases of orcharding and field farming, including pruning, grape culture, fertilization, cultivation, irrigation, harvesting, pest control, etc. It requires the making of decisions and exercising judgment, particularly with respect to timing of various operations. One must also keep abreast of the times and informed on modern devices, methods and developments.

2. Planning and directing the work and activities of the field force.

3. Coordinating custody and discipline with field operations.

4. Coordinating with the Superintendent of the camp and his staff in the makeup and assignment of crews in the field.

5. Assignment, direction, and supervision of foremen of inmate crews performing farming and other work operations.

6. Coordinating with Superintendent activities of Columbia Camp with those of Army Engineers.

Responsible for:

1. Custody of inmates assigned to field operations.

2. Safety of inmates and personnel engaged in field operations.

3. Estimates of requirements for equipment and supplies.

4. Custody and maintenance of equipment and supplies used in field operations.

5. Custody of materials used in operations, i.e. seed, gasoline, oil, insecticides, etc.

6. Estimate production.

7. Custody of crops harvested from the areas together with proper acccounting for same.

8. Operations in the absence of Co-worker.

9. Supervision of the following employees: Four Senior Foremen, Eleven Foremen, Two Truck Drivers, Two Farm Helpers

My duties and responsibilities of an average day as Farm and Field Supervisor:

I. Meet Foremen and Workers at gate at 7:30 so as to:

A. Check absence of Foremen and Workmen.

B. Check materials and equipment with men in charge of same.

C. Make any change in plans made necessary by inclement conditions, etc (for example strong winds interfere with spraying operations.)

D. Discuss problems with Foremen when such arise and give necessary instruction, direction and advice.

II. See that there is no unnecessary delay among the Foremen when:

A. Checking out their crews.

B. Organizing materials and equipment.

C. Leaving for the job assignments.

III. Assign, instruct and supervise truck drivers and farm helpers who are hired to carry on operation s,i.e. trucking and transfer of materials, equipment and farm produce, tractor driving for cultivation, fertilization etc, when and where inmate labor cannot be used.

IV. Morning conference with Superintendent, Senior Field Foremen and Officer of the Day to:

A. Coordinate all plans of field and camp operation.

B. To anticipate and plan for change due to weather, illness, vacations, etc.

C. Plan equipment and material needs, procurement, use, care, and repair, storage, etc.

D. Discuss any field custodial problems and plan job performance to provide for rehabilitation and vocational training of inmates.

V. Daily inspection tour of field operations to:

A. Check job progress of field crews and civilian irrigators, truck drivers and farm helpers.

B. Investigate material and equipment needs of each crew and civilian worker. Make necessary arrangement to supply same. Also arrange for safe and proper use, care, and storage of such material and equipment.

C. Make production estimates.

D. Study operations to prevent delay, eliminate, combine, rearrange and simply details ofjob.

E. Observe each foreman s inmate handling and supervision with regard to discipline, safety, job performance, etc.

F. Instruct, assist, and encourage foremen and civilian workers, when necessary.

VI. Daily inspection of farm lands, orchards or vineyards to:

A. Determine needed irrigation, cultivation, fertilization, pruning, pest control, etc.

B. Test ripeness of vegetable, fruit, grain, etc. to decide what day to start harvest or give any other attention needed.

C. Make crop estimates.

D. Plan custody of c~ops and other produce, equipment, etc.

VII. Daily inspection of work operations being done for Army Engineers. Also occasional inspection tours of operations with representative of Army and/or other area departments.

VIII. Coordinate field operations, when necessary, with safety council and/or fire department, i.e. burning weeds or orchard brush, etc.)

IX. Meet Foremen at gate after work and notify them of any changes in plans for following day.

THE GALLERY

|

|

|

page started: 03/19/02

page updated: 03/29/02

E-mail the webmaster

Columbia Camp